SINKING HOUSES

Venice is built on unstable ground. Facades are distorted, floors uneven and cracks are numerous.

Casa a San Giobbe before restoration (photo Joaquim Moreno 1997)

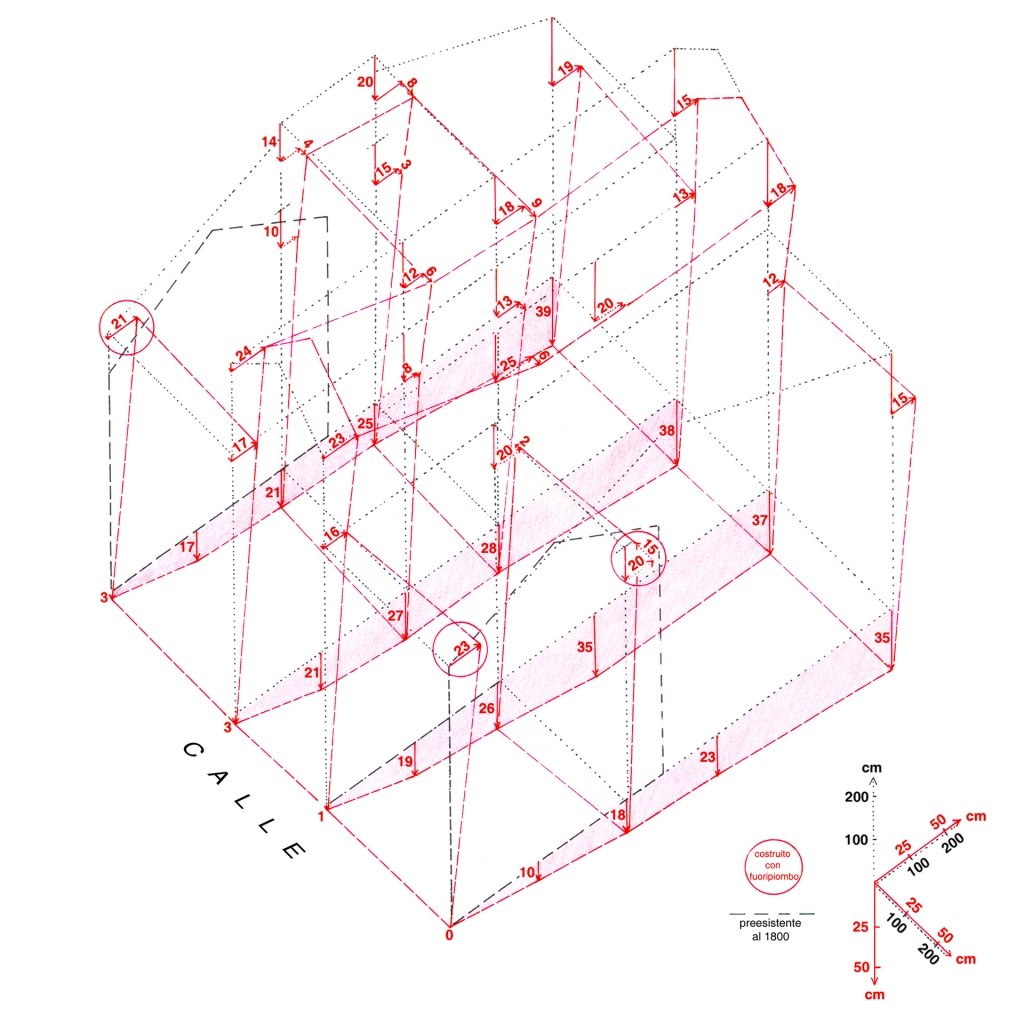

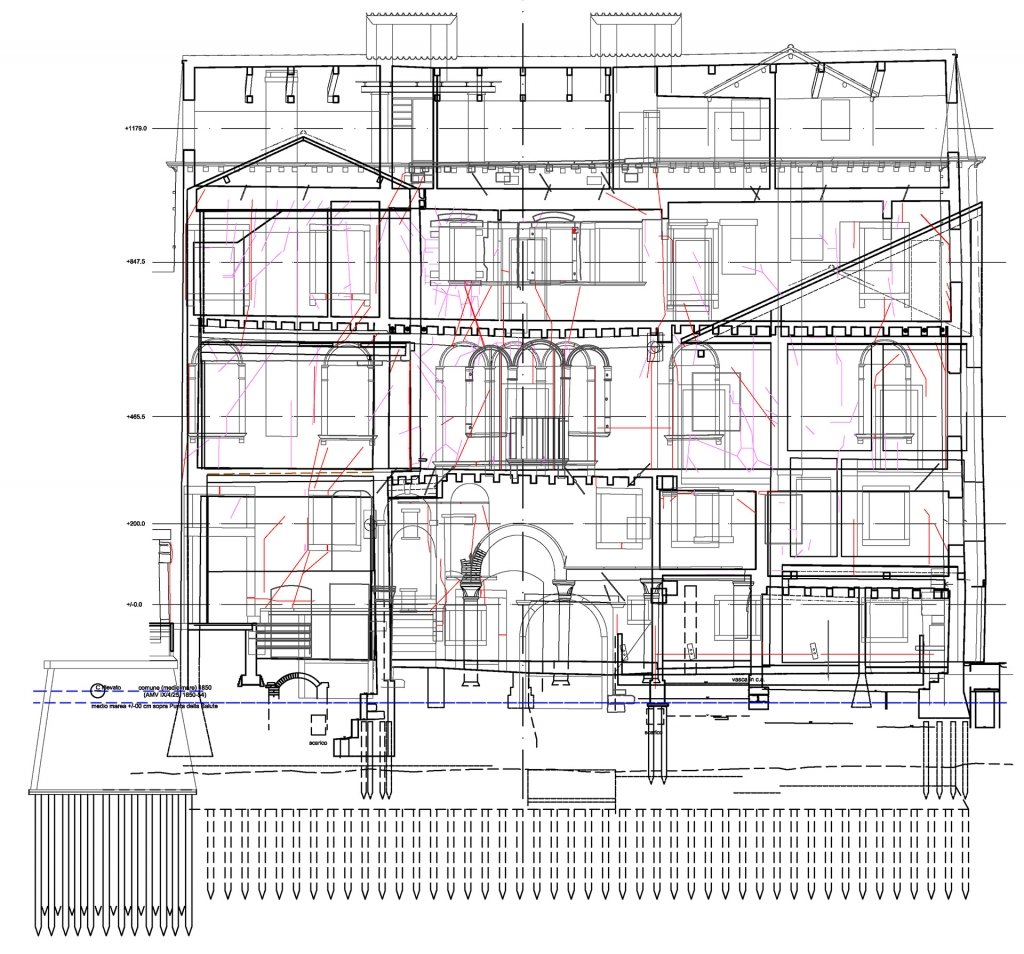

Precise surveying and monitoring enables the origins of this deformations to be understood and indicates if facades where already built tilted inwards to avoid a more dangerous tilting outwards. Iron ties, original or added, hold floors and walls together.

Deformations Casa a San Giobbe (Leo Schubert 2006)

Much of the deformation took place during construction (brick and stone courses are uneven at lower levels and become more and more horizontal at each successive floor: evidence that the foundations were settling during construction. The later addition of floors or new constructions nearby could cause significant additional settlements.

Rio di Santa Caterina (foto Leo Schubert 2015)

The deformations of several decimetres that we measured in our surveys took centuries or very traumatic events to develop and are usually not a cause for alarm (the much-debated sinking of Venice is another topic: subsidence in the highly industrialized post-war period was mostly due to the extraction of cheap ground water for industrial use and the phenomenon seems to have arrested since restrictive laws were introduced).

If the foundations do not show any more differential settlement, localized actions, like tying tilted walls to the floors and roof etc. will often be sufficient to improve resistance to earthquakes (the most devastating one for Venice being recorded at the beginning of the 16th Century).

Things become more alarming if new cracks appear or old ones start to reopen.

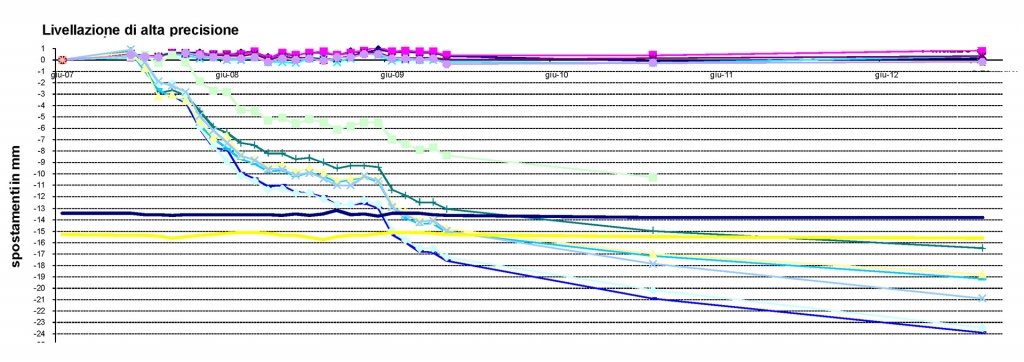

A very efficient way of measuring ongoing deformations is periodic high precision levelling (1/100 of a mm). Tilting and cracks can also be monitored, but in most cases they show the consequences of horizontal settlements of the foundations.

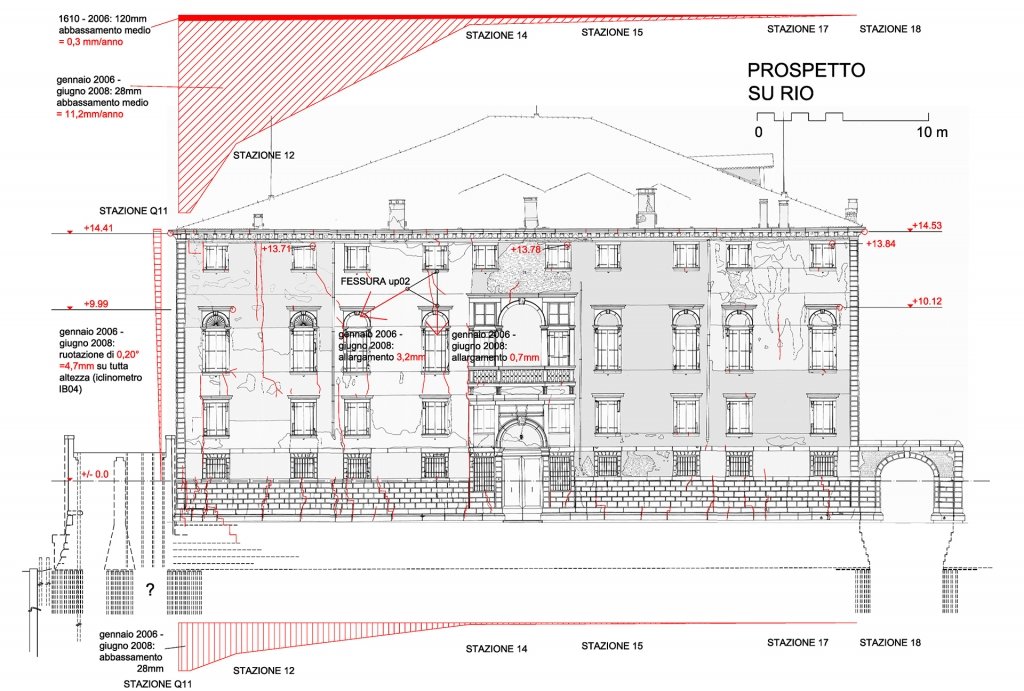

High precision levelling over a period of 5 years (palazzo Merati, Leo Schubert)

Why do some foundations still settle in Venice? Equilibrium in the unstable ground is very delicate: although the wooden piles and planks used by builders until the 19th century to consolidate the ground under load-bearing walls are mostly found in a good state of conservation, they rarely reach the deeper and more resistant layers as do modern foundations (on concrete pillars, for example). Foundations along canal-sides are constantly being eroded by the activity of the tides and the waves generated by motorboats. The construction of septic tanks (the only way waste water is treated in Venice and mandatory for the frequent transformation of housing into hotels and restaurants) close to foundations or the carelessly executed consolidation of waterfronts are other causes.

The latter was the cause of the settlements and consequent crack formation in the following constructions we happened to monitor:

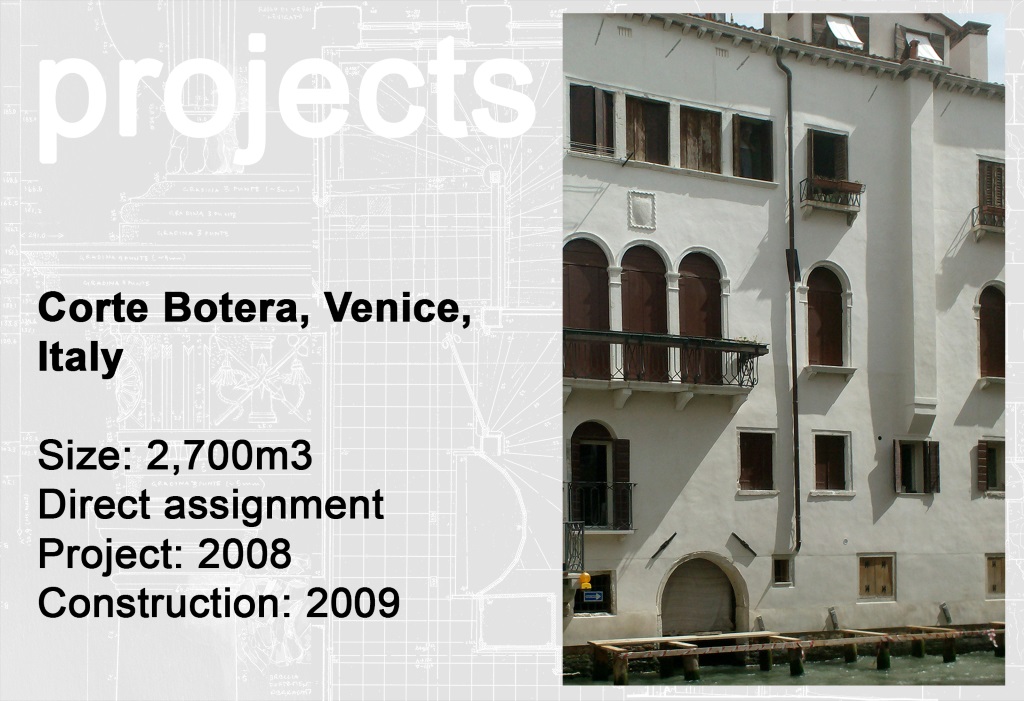

Damage assessment Corte Botera ( Leo Schubert 2008)

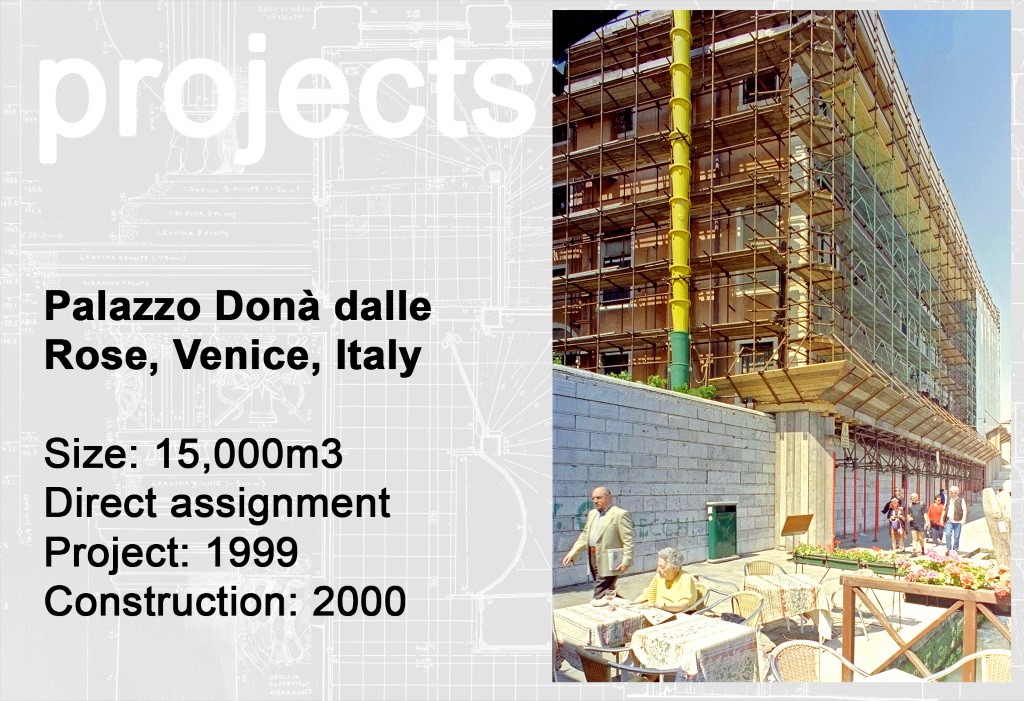

Damage assessment Palazzo Donà dale Rose ( Leo Schubert 2008)

REINVENTING SPACE IN A HISTORIC CONSTRUCTION:

Venetian residential constructions are particularly well suited to have a long life (and are therefore very “sustainable”), not only because they were built with skill and good materials but also because they have very flexible layouts: to avoid load concentration on the unstable ground (see SINKING HOUSES), only a strict minimum of walls were built to carry floors supported by very narrow wooden beams with spans of between 5 and 8m . Partition walls were made of wood covered with plaster. These light partitions can easily be moved. Often, only the long sides of the central hall have load-bearing walls, while the short sides consist of huge windows.

Portego casa a San Giobbe (photo Vittorio Pavan 2006)

Small houses often repeated the pattern used in patrician palaces from the 16th to the 18thcentury, where the central hall served to accommodate several hundred guests. During less prosperous periods, these large rooms were often divided into smaller ones, especially during the 19th century, when Venice became home for a crowded, but mostly poor population.

The following two projects show how generous this layout is, and how easily a new (or old) spatial distribution can be created or recreated.

REVERSIBILITY OVER CENTURIES: Borgoloco Pompeo Molmenti

Borgoloco Pompeo Molmenti (photo veniceteam 2015)

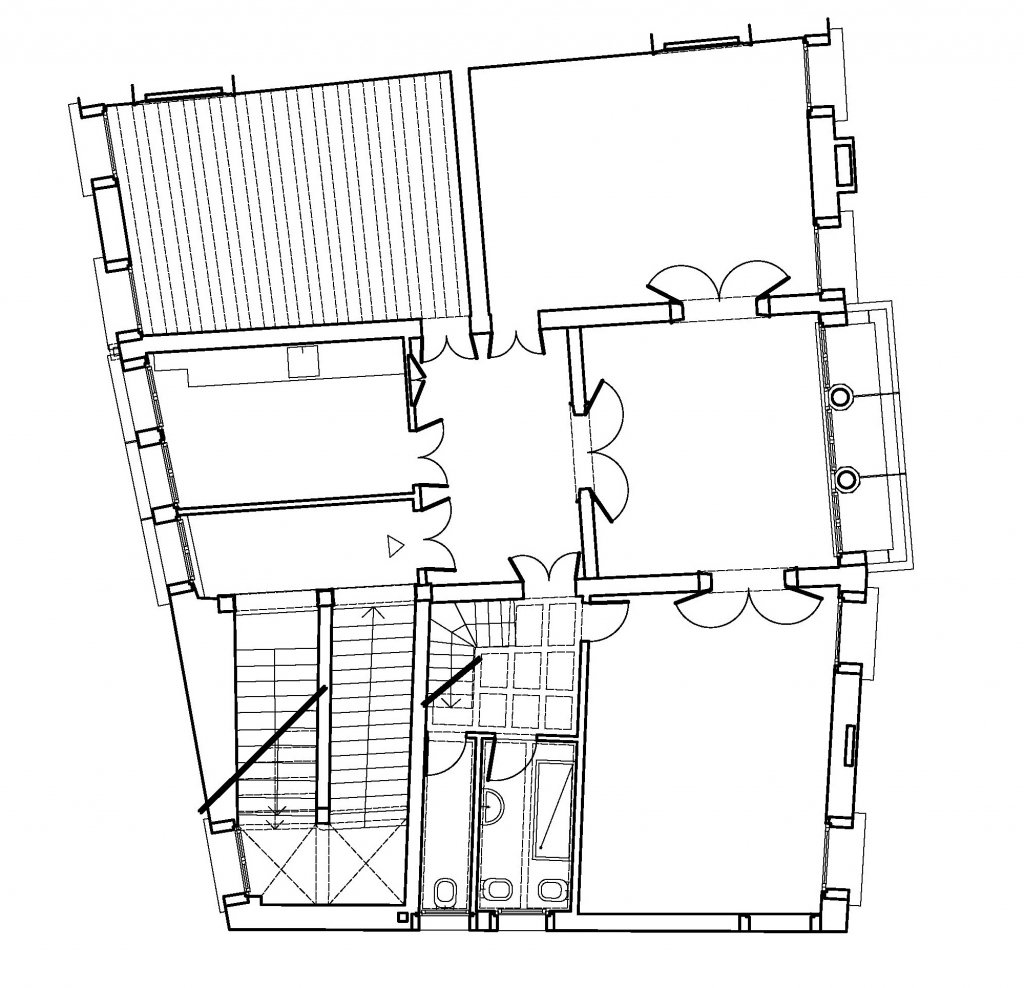

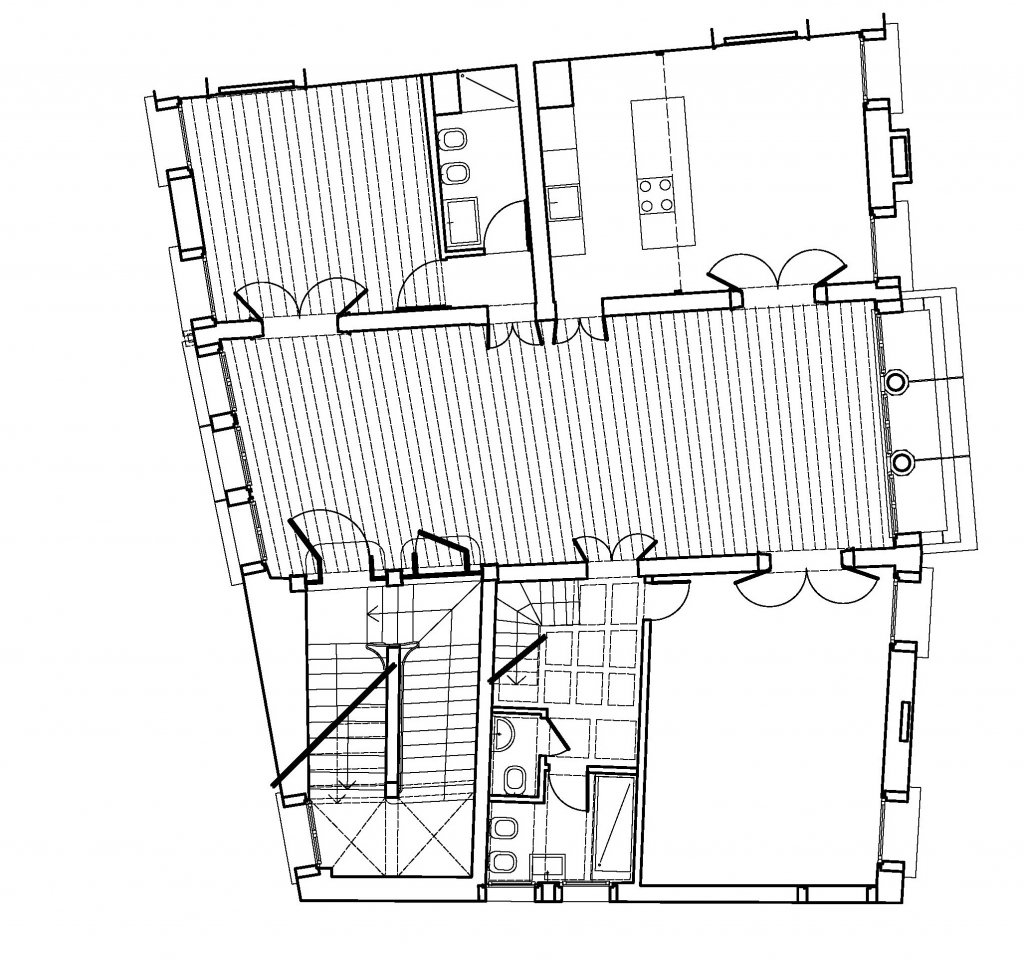

Borgoloco (public courtyard) Pompeo Molmenti is flanked by a row of nearly identical small buildings, built after 1500 and reusing older walls. They have been through several transformations (in the 18th century two were joined by opening doors in the party wall and modifying the staircases). In the 19th century both constructions were separated again (simply by bricking up the doors, leaving the marble jambs in place) and in 1930 wooden partition walls were erected to transform the central hall into a landing for the stairs, a kitchen, the entrance and a relatively small living-room.

Borgoloco Pompeo Molmenti present state (veniceteam)

The narrow kitchen and the large, unlit entrance hall are unsuitable for the use of the present owners. Since it is easy to remove the 1930s partition walls, the magnificent, 4 m-wide and 11m-long central hall will be restored and the kitchen moved to another place. The stairway has to be modified to make each apartment independent (the main hall gave common access to all the other rooms, including the flight leading to the upper floor). The solution proposed for the stairs is current in Venice, where condominium ownership dates back to the Middle Ages and most buildings were divided through inheritance arrangements several times over the centuries.

Borgoloco Pompeo Molmenti project (veniceteam)

BRINGING LIGHT INTO AN OLD PALACE: Palazzo Soranzo

Palazzo Soranzo prior to renovation (veniceteam)

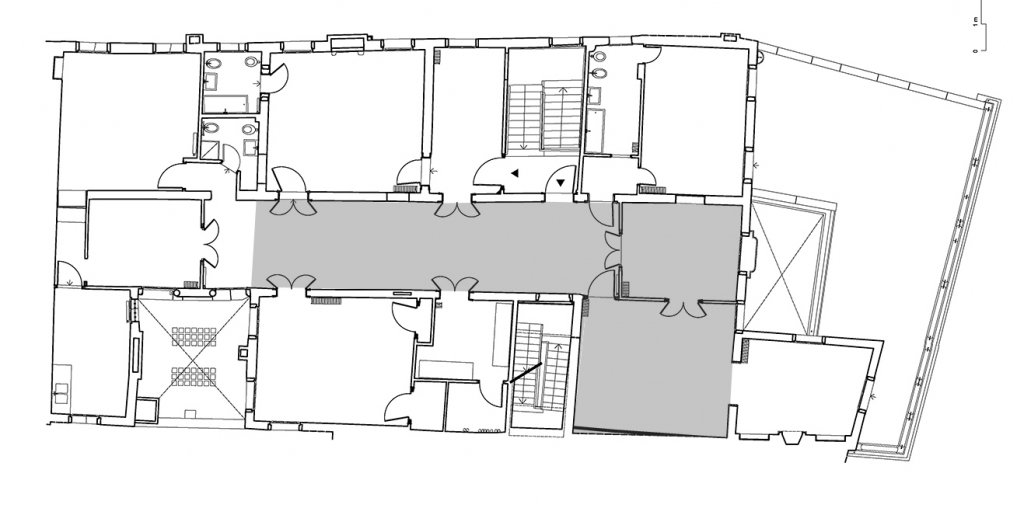

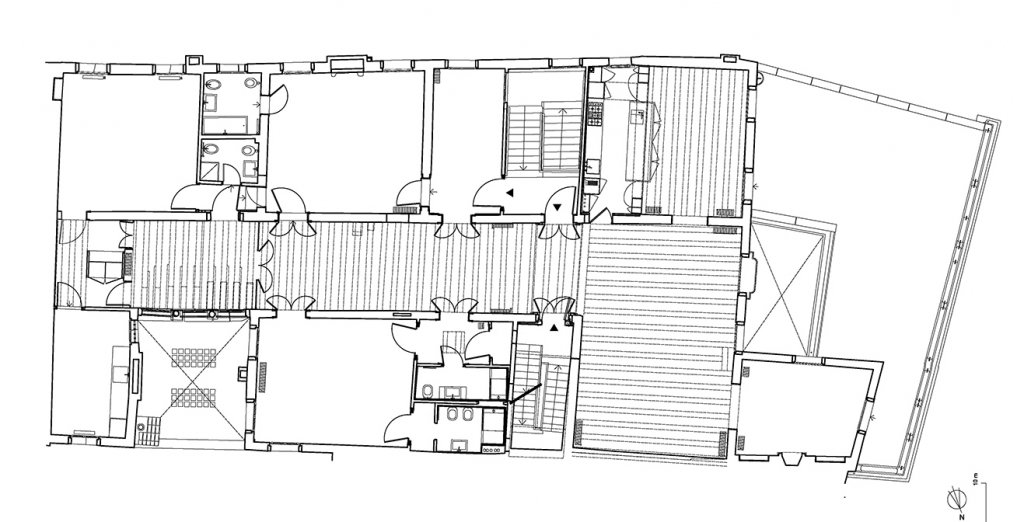

Again the second floor of this construction has undergone several transformations to accommodate numerous families for almost 6 centuries. Added in the mid-15th century (some previous roof beams are still incorporated into the masonry) and covered with a ceiling able to carry at least 1 other storey, its layout is typical of late “Gothic” palaces: an L-shaped main hall (grey) with rooms on each side of the longer part of the L.

At the end of the 18thcentury a third storey was added above the main façade and the Gothic window that illuminated the L-shaped hall of the second floor was replaced by a “modern” but smaller, arched window. Probably it was intended that the interior of this floor would be transformed too, but the Napoleonic wars must have stopped construction.

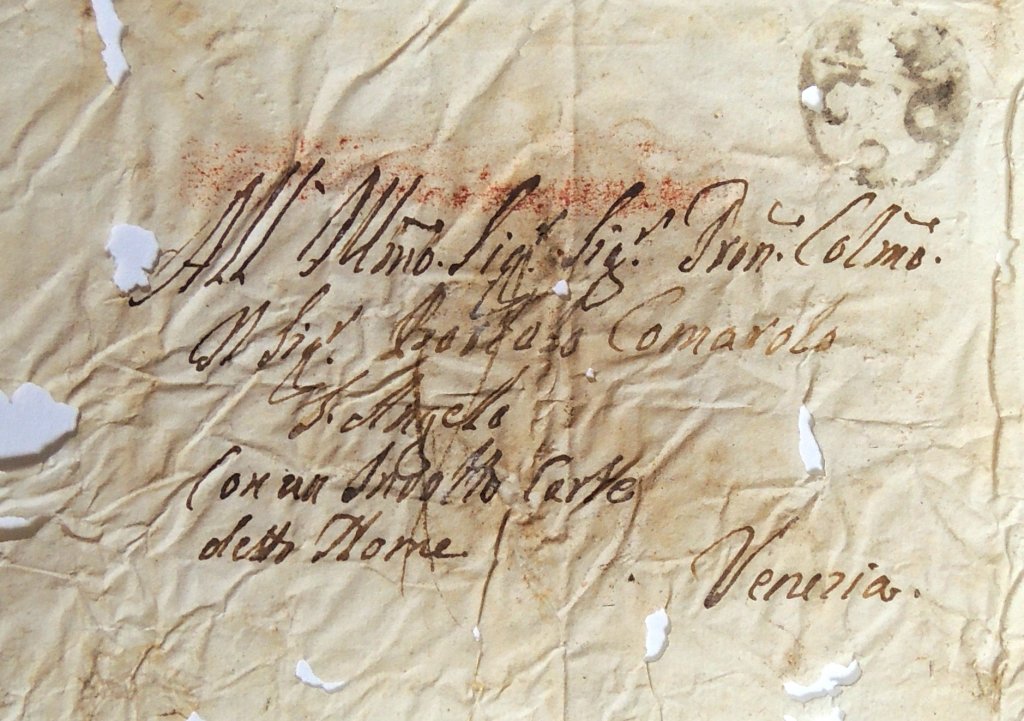

In 1804, after the overthrow of the Venetian Republic, a certain Comarolo, who had rented the building from the Giustinian family, bought it and used old letters and other papers from his father to fill the cracks in the beams of the ceiling of the hall before repainting them grey.

The discovery of these documents enabled a reconstruction of the floor’s history, showing that in the early 19th century the hall was still L-shaped and only in the mid-19th century, after new owners bought the construction, were ceilings lowered and partition walls erected to create two drawing rooms along the main façade and a long, badly illuminated corridor in what was formerly the longer part of the L.

Palazzo Soranzo prior to renovation (photo veniceteam)

Traces on the floor, partially demolished and reconstructed plaster ceilings and bricked-up windows show that the position of these partition walls changed considerably with each generation of new owners.

Palazzo Soranzo during renovation (veniceteam)

The aim of the present restoration was to reopen the L-shaped main hall together with the bricked-up windows to allow light once again to enter the 25 m-deep living area.

Palazzo Soranzo after renovation (photo veniceteam)

The kitchen dating from the 1950s, situated in the rear of the apartment, was kept as a laundry-room and a new kitchen was created in place of a former bathroom: a former bedroom thus became a dining room with access to the spacious 80m2 terrace.

Palazzo Soranzo after renovation (veniceteam)

IMITATING BRICKS ON BRICKS

Palazzo Donà della Madonata in 1900 (photo Naya) and prior to last renovation (photo veniceteam 2010)

How were medieval constructions “finished”? Palazzo Donà della Madoneta was last restored in the 1940s, when a 19th century plaster with fake marble decoration was removed from the façade on the Grand Canal to show the “original” brick curtain wall dating back to the construction of the building sometime after 1290. The mortar joints show very carefully made incisions and one might think that this was the finish that medieval builders wanted to be seen.

When the plaster applied in the 1960s to the remaining facades was carefully removed, interesting stratifications appeared (see READING A FAÇADE) and a microscopic fragment of thin red-painted plaster gave a hint about possible decoration that had been lost over time.

Palazzo Donà della Madonata east elevation, fragments of decorations (photo veniceteam 2012)

Inside, stratigraphic analysis revealed mostly 19th/early 20thcentury decorations, as in the main staircase (former courtyard) rebuilt in this period, where coloured patterns imitating medieval wall paintings emerged (at a first glance they were taken for “original”, but further investigations showed that they were applied on industrial bricks). Since the survey revealed that the “piano nobile”, the main hall facing the Grand Canal, was formerly reached through a monumental door at the top of what must have been an outside staircase mentioned in an archive document from 1425 and that the modern finishing layer probably concealed precious information about the medieval palace, the plaster was removed.

Palazzo Donà della Madonata staircase after renovation (photo veniceteam 2012)

Once the plaster was removed, the monumental door, in line with the only pilaster of the loggia (which is otherwise made of reused, antique columns in marble from Marmara) revealed a gratifying surprise: the stone lintel is surmounted by a an arch made of carefully polished bricks with millimetric joints and a geometrical decoration carved into the bricks.

Palazzo Donà della Madonata decorated lintel (photo veniceteam 2012)

But there is even more: the bricks of the arch are covered with tiny fragments of red painted plaster the same as those already observed on the outer facades but with larger areas perfectly preserved: fake bricks painted with great care on perfectly worked and jointed bricks.

We know these decorations were frequent in the 15th and early 16th century and they are beautifully depicted on paintings of that period (see for example Carpaccio’s cycle of the Miracle of the Holy Cross, now at the Accademia Gallery) and there are fragments conserved on several façades and inside churches. A brilliant architect reused them in 1905 for his own house, the casa Torres on Rio del Gaffaro, and specialized literature calls it regalzier.

Further investigations might tell if the regalzier of Palazzo della Madoneta was added one or even two centuries after its construction or if this apparently strange taste for painting bricks on bricks persisted in Venice over several centuries.

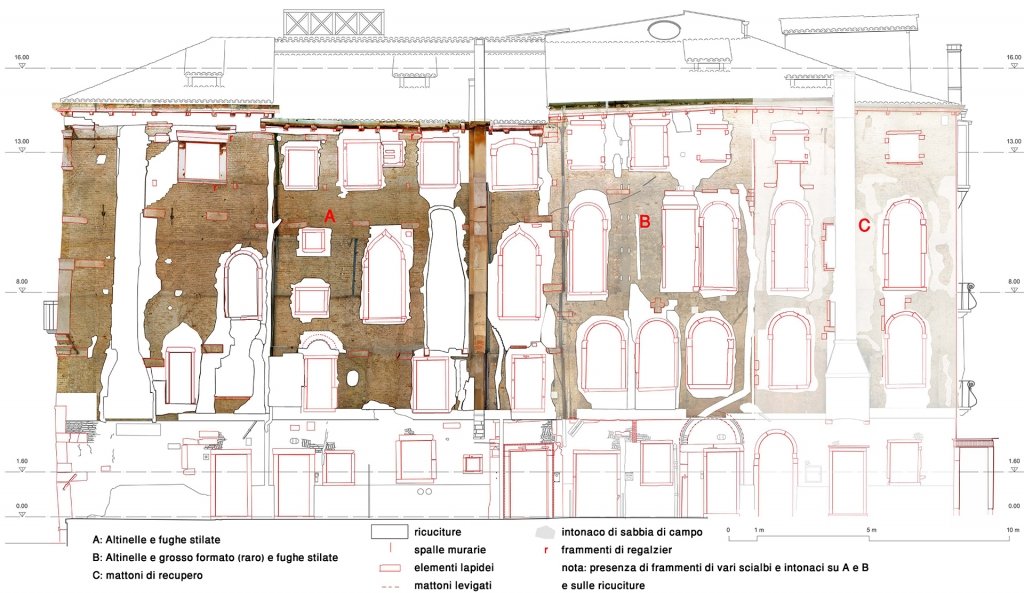

READING A FAÇADE

Palazzo Donà della Madonata, façade at right angles to the Grand Canal prior to renovation (veniceteam 2011)

Historic buildings get transformed with every generation. It is challenging to attempt a mental reconstruction of the form buildings assumed at a precise moment in time or to understand the aesthetic intentions, the constructional constraints or social needs of a historical period (and therefore to position ourselves). Historians ideally try to overlay written or iconographic evidence with archaeological inquiries. Unfortunately, in most cases, only one of these approaches is possible and the interpretation is therefore partial.

Palazzo Donà della Madoneta passed by inheritance through many owners between1425 and the end of the Venetian Republic in 1797. From 1290, the date of the earliest archival document describing a construction in this position on Grand Canal, until 1797, it had never been divided and no legal controversies about its ownership are recorded in the State Archive (special thanks to Jan-Christoph Röessler who did the research). Though few written documents have emerged and only a few sketches, paintings and historic photographs have been found, we can rely on numerous direct observations that emerged during renovation work in order to understand certain aspects of its history.

The now removed plaster on the façade at right angles to the Grand Canal, originally painted orange and dating from 1960, concealed a considerable quantity of information.

Palazzo Donà della Madonata, façade at right angles to the Grand Canal during renovation (veniceteam 2012)

What seemed to be a later addition turned out to be a construction already mentioned in 1425 and owned by the Emo family when they bought the entire block (see B and C, figure above): the part closer to the Grand Canal (B) was built with bricks similar to those used for the structure facing the Grand Canal (A) and might even be older; the rear part (C) was an addition built with reused bricks of different formats. Both have undergone substantial transformation, as shown by closer analysis of the windows and their surrounding walls. During the 16th century 4 arched windows with Renaissance mouldings were inserted into the older part (B)and in the 18th century both parts (B and C) were joined with the addition of 7 arched windows and a cantilevered fireplace. On this occasion, older windows in the rear part (C) were bricked up or covered by the chimney and the Renaissance mouldings (in B) were cut away so that all the windows in B and C matched stylistically.

Unsurprisingly only one of the 28 present windows is still in its “original” place (on the top right in C, see figure above). All the other windows have been bricked up, added or even transformed as seen above. The part facing the Grand Canal (A) retained its stylistically different windows. Here, the only other window contemporary with its surrounding wall was bricked up in the 19th century (the top left window, see figure above, with an architrave actually dating from the XV century) and the two chimneys, one of them still visible in a 19th century photograph, were probably removed as late as the 20thcentury (when central heating was introduced).